The Correct Lessons to Learn From Deadly Train Accidents

Be careful not to learn the wrong lesson.

By Hexel Colorado on August 6, 2022

What happened in Ontario, Canada?

On August 2nd, four-year-old Mitchell and her cousins were playing at a park near their apartment when they wandered off chasing butterflies. Unbeknownst to their family, train tracks are at the far-end of the park. Although fencing ran along the tracks, the kids wandered to a fence opening.

The kids entered, stepped onto the tracks, and played for some time. Suddenly, the train horn blared. The cousins dashed off to safety, but Mitchell froze in place. Fifteen minutes later, parents were called. They rushed from their apartment, searched the park, and found the kids where they wandered. There was nothing they could do; Mitchell had died on impact.

If you’re like me, tragedies like this make your head spin with questions. The most important question: how do we prevent this from happening again?

Choosing between blame and understanding

To learn how to prevent another tragedy, there are two paths we can take:

- Determine who is to blame for what happened

- Understand how and why it happened

Some might not see a difference. If we figure out who’s to blame for what happened, won’t we find out how and why in the process? Maybe. But each path results in a different diagnosis. If we choose to assign blame, we have three choices:

- The child who was killed

- The family who survived

- The train that hit the child

Blame leads to an easy (but wrong) solution

Blaming the child or the family won’t prevent the next tragedy. On the other hand, blaming the train feels productive. Removing the train is 100% effective at preventing another person from being hit by that train. As the saying goes: the simplest solution is usually correct. Usually.

However, the easy solution of removing the train solves one problem and creates several more. Most people who relied on the train for travel will likely switch to driving a car. Considering road traffic accidents are the leading cause of death in the United States, we are 50 times more likely to die on the highway than in a train, and 46,000 people die every year in crashes, our easy solution will endanger more people than it saves.

One train has the capacity of 177 cars. Removing the train puts more cars on the road, reducing public safety and increasing pollution.

One train has the capacity of 177 cars. Removing the train puts more cars on the road, reducing public safety and increasing pollution.

Understanding leads to the right solutions

To learn the right lesson, we must put aside the question of blame and focus on discovering how and why the tragedy occurred. There are elements of this story that, if any were missing, tragedy might have been avoided. What are the critical story elements?

- An accessible opening in the fence.

- The children entering the opening.

- The children standing on the tracks.

- The child freezing on the track.

- The children not having adult supervision.

- The parents not knowing about the tracks.

- The train not stopping before impact.

- The train moving at a lethal speed.

Having identified all this, we must acknowledge three things. First, fixing any one of these elements could avoid tragedy. For example, if the train was not moving at lethal speed, it could have avoided impact. Second, each element has varying degrees of effectiveness. For example, the parents could have been informed about the tracks, but there’s no guarantee they would teach sufficient caution to their children. Third, every fix has a cost. For example, an education program costs time and effort to produce a learning curriculum.

Knowing all this, what is the right solution? Fix everything that we can afford, starting with the highest effectiveness and lowest cost. Ranking our fixes might look like this:

- Install fencing to close the opening. (High effectiveness, low cost)

- Educate children on train safety by incorporating it into school curriculum. (Medium effectiveness, low cost)

- Educate parents on train safety through an awareness campaign coordinated between the transit agency, property owners, and city. (Medium effectiveness, medium cost)

“Cost” is not just money. When it comes public safety, there is no limit to the money we can spend. “Slow down the train” and “remove the train” did not make the list because the increased risk of car death is a cost we can’t afford.

Don’t discount education — it really does make kids safer

Education programs might not be as effective as physical barriers, but empirical evidence proves that it works. In 2012, the Metro in Melbourne launched a public awareness campaign on train safety. They produced cartoons and songs aimed at children, which were played on radio, television, schools, and on video screens at transit centers. The awareness campaign was a wild success: within one year, Melbourne saw a 21% reduction in train incidents.

“Dumb Ways to Die” is a light-hearted, comedic song to raise awareness for train safety. The viral video hit 20M views in one week and gained national news coverage. It reached top billboard charts in major countries.

Practice understanding more incidents

Observing the how and why behind additional accidents— the collision in Missouri between Amtrak and a dump truck, the collision in California between Amtrak and a car, and a string of train-pedestrian collisions in Tucson, Arizona — I learned that they share multiple critical story elements:

- There were no cross guards at intersections.

- There was no fencing between railway and public space.

In June 2022, an Amtrak train carrying 282 people collided with a fully loaded dump truck. The one truck driver and four train passengers died. The intersection had no lights or cross guards.

In this photo from Tucson, Arizona, we see there is no separation between the buildings and the track. Also, notice how the train comes around a blind curve.

Tucson needs fencing and mid-block pedestrian crossings

In Tucson, Arizona, there were 4 pedestrian deaths in July alone, and 10 in the last 12 months. Pedestrians walk across the tracks on a regular basis. On Google Maps, we can see several homes, parks, and businesses lining either side of the track.

Fencing is entirely missing for most of the railway. New fences are an obvious place to start but fencing alone is not enough. If you lived next to the track, would you rather walk around the fence for 20 to 30-minutes, or would you take 3-minutes to jump the fence to get to work? Many may choose to jump. I wouldn’t be surprised if desire path holes were cut into fences days after installation. Mid-block pedestrian crossings can disincentivize dangerous behavior.

Mid-block crossings are used on roads to make it safer for pedestrians to take shortcuts. A similar technique can be used on railways to allow safe passage by pedestrians.

Grade-separating the railway

There’s a strong case in Tucson for more grade-separation of the railway — this means either trenching the railway below ground (so people can cross above) or building overpasses to elevate the rail (so people can cross below). While certain parts of town warrant grade-separation, it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution.

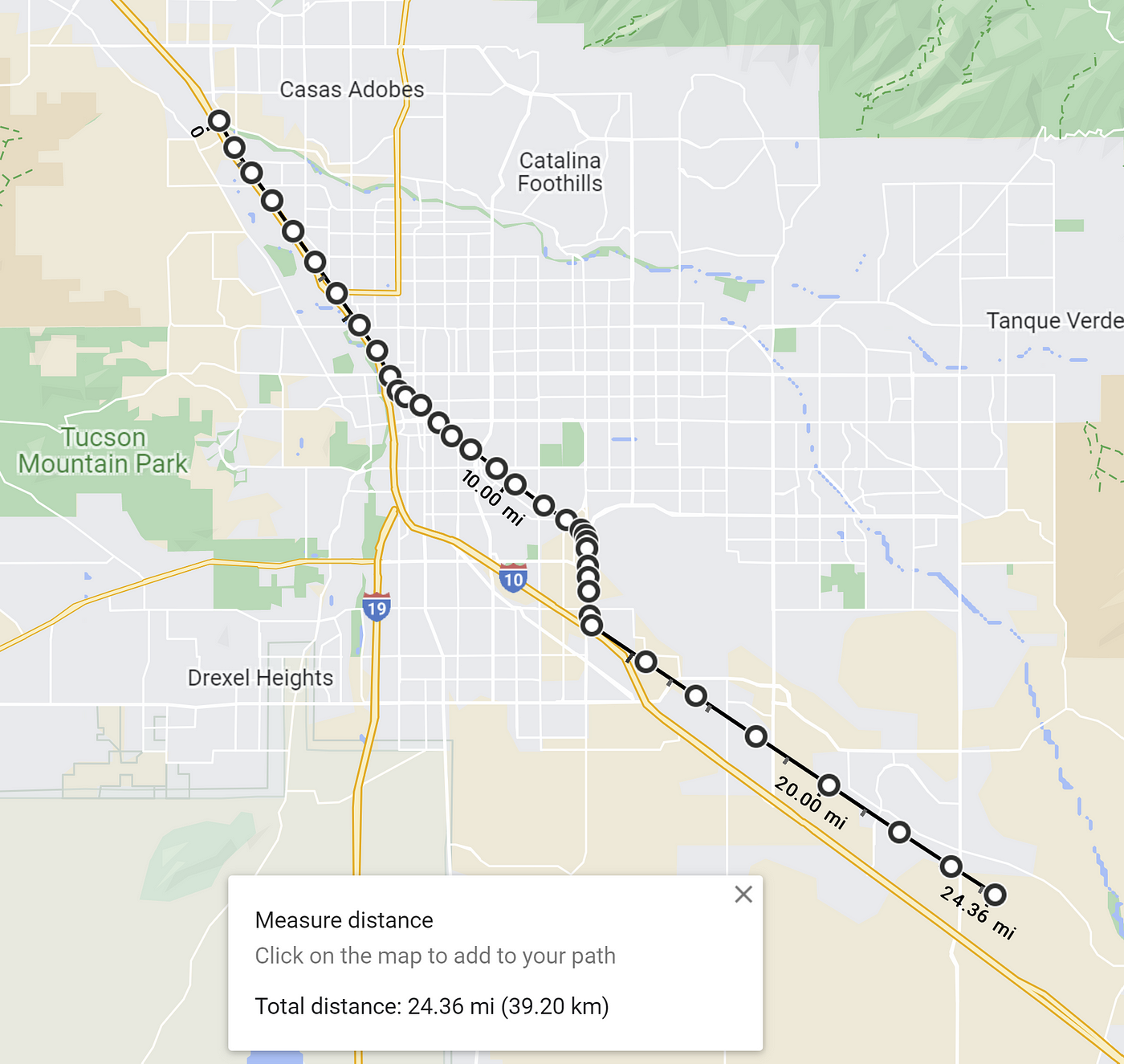

I measured roughly 24 miles of railway cutting through the city of Tucson.

Elevating a train amplifies its noise, which may be undesirable in residential neighborhoods. If you thought electric light rail is loud, remember that Amtrak runs heavy diesel trains. It usually isn’t feasible to build a sound barrier for an elevated railway. In addition to capital, your assessment of cost should account for noise, construction, land-use, and potential effect on property values.

Elevated railways in Dallas, TX emit more noise than at-grade railways.

Elevated railways in Dallas, TX emit more noise than at-grade railways.

When it comes to trenching, I plan on writing a blog post that goes into greater detail on its hidden costs. For now, just remember that in addition to the high monetary cost (typically hundreds of millions of dollars) trenching also has a high cost in land, construction time, flood risk, and energy usage.

Pedestrian overpasses and underpasses

Pedestrian overpasses and underpasses are options to consider. Overpasses require sufficient area at both of its ends to provide a gentle, ADA-compliant slope. It needs to be sturdy enough to withstand extreme weather and enclosed to prevent people from accidentally (or intentionally) falling off. If the geometry of the land allows for it, pedestrian overpasses are a nice solution.

The Paleisbrug bridge in The Netherlands. Photo: Jannes Linders Fotograaf

The Paleisbrug bridge in The Netherlands. Photo: Jannes Linders Fotograaf

In a similar vein to trenched railways, pedestrian underpasses are a solution that are easier said than done. Lighting, drainage, flooding, debris accumulation, accessibility, and safety are overlooked underpass concerns.

Source: pedbikeimages.org — Dan Burden (2006)

Source: pedbikeimages.org — Dan Burden (2006)

Too many crossings have no pedestrian protection at all

I read a lot of train crash stories. For this article, I searched specifically for collisions between trains and minors under 18 traveling on foot. I had two disturbing observations.

First, while studies report it common for general pedestrians to circumvent pedestrian gates before a collision (Compilation of Pedestrian Safety Devices In Use at Grade Crossings, Page 23), I didn’t find a single story of a youth dying in such a way. In stories I read, the child walked unencumbered into the path of a train. This was evident across every story because of the second thing I observed…

A 14-year-old was killed by train while walking along these tracks in Edgewater, Florida.

A 14-year-old was killed by train while walking along these tracks in Edgewater, Florida.

… every crossing had zero pedestrian protection of any kind. The street view above shows the tracks that a Florida teen was walking on when she was hit by a train. There were no fences, signs, or barriers to discourage walking on the tracks; they’re just as inviting as the road parallel to it. An elementary school is behind this view.

In the upper-left hand corner is Killeen High School. In the bottom-right are trailer homes. Train trucks tracks run between, with no fencing or barriers in site.

In the upper-left hand corner is Killeen High School. In the bottom-right are trailer homes. Train trucks tracks run between, with no fencing or barriers in site.

In March of this year, a 15-year-old was hit by a train while jumping the tracks on her way home from school. Again, no fences or barriers to prevent or discourage this. This reminds us to ask not just how, but why tragedy occurred. Given the school’s proximity to homes on the other side of tracks, a mid-block railway crossing with proper gates and warning lights would allow youth to make the shortcut safely. Who knows how many students still dangerously leap the tracks to and from school?

Train tracks are on top of the ridge. You can see the cross where a 16-year-old was killed after he climbed up the ridge and onto the tracks.

Train tracks are on top of the ridge. You can see the cross where a 16-year-old was killed after he climbed up the ridge and onto the tracks.

A common assumption is that grade-separation eliminates risk at crossings. The picture above is a sad reminder that there are no such guarantees. There was no fencing to deter a Kentucky teen from taking the fun way to the other side over the ridge. No signs warned of an active train track waiting at the top of the ridge, just out-of-view.

Conclusion

I’ll end this with a “good news — bad news — good news” sandwich.

Trains are forty-five times safer for pedestrians than cars

The good news is that your chance of being hit by a train as a pedestrian is still incredibly low compared to being hit by a car. Across Texas, in 2021, pedestrian deaths from trains versus cars were 57 to 841; injuries were 62 to 1,470.

Trains are also safer on the inside. While only 6 train passengers died in 2021, the grand total car deaths in Texas were 4,573, making our state the highest in the nation. The more people enabled to make the switch from cars to transit, the safer we all will be.

Any number of deaths is too much, and it’s not getting lower

The bad news is that we’re not making much progress on getting the number of train-pedestrian deaths any lower. With Houston Metro being the most collision prone light rail system in the nation for the last five years, the question needs to be asked if we’re doing enough to hold trains to the same VisionZero ideal we dream for cars.

The more we ride rail, the smarter we get at making it safe

I’ll close with these encouraging conclusions from a Pedestrian Safety at Rail Grade Crossings research paper published in 2016:

- States with substantial passenger, commuter, and freight rail operations are leading the effort to develop guidelines and engineering standards for safety improvements.

- Strong local advocacy is the most important factor, other than adequate funding, behind effective education, outreach, and enforcement safety campaigns at pedestrian-rail grade crossings.

- Education and enforcement campaigns must be sustained over time and place and use a variety of techniques to engage the user community. Campaigns for commuter and light rail grade crossing safety can be relatively more effective with the active participation of the transit agency and a captive local audience exposed to the frequency of transit operations.

- It is likely that pedestrian safety at rail grade crossings will benefit in the longer term by the increasing consistency in standards for warning devices and treatments among organizations responsible for this task.